In the 19th century, most families had a very different relationship to death than we do today. Children encountered death on a regular basis; it was impractical to conceal it from them. Death was a regular part of community life. Most people died at home, and were prepared for burial by family members.

While exploring books published by the American Tract Society in Boston, I’ve encountered a few that focus on the lives of deaths of children. While I would not recommend these books to today’s young readers, they contain valueable historical insights. This meandering post covers three interesting examples. For a detailed overview of this genre, see the article titled, A Communion of Little Saints, Nineteenth-Century American Child Hagiographies by Diana W. Pasulka.1

Samuel Brenton Burge

Last year, I acquired a small chapbook titled Patter written by Mrs. Frances Irene Burge Smith. It is a fictional children’s story about an enslaved woman that was published in the 1860s. To be frank, I don’t like the story, but it is still a useful artifact.

This small volume is part of a series called The Fanfan Stories. They were published individually as chapbooks and collectively as a hard cover book. I recently acquired the latter since I hoped the collection would include more stories with Black characters, but I was somewhat disappointed in that regard. I did however, discover something much more interesting!

American Tract Society’s 50th annual report.2

I assumed all the stories in the collection would be fictional, but the first two are clearly based on the author’s real life.

The first story is titled Merry Christmas at Wickdale. Despite her paltry attempt at obfuscation, the story is clearly about her childhood in Wickford, Rhode Island. She wrote openly about the town in later years.

The story contains a lovely description of the old church where her father, Reverend Lemuel Burge, was a minister. An image of the church appears on the cover one of her later books titled Old Wickford.

The second story in the collection is titled Little Samuel’s Ministry and it’s about the author’s deceased brother. It chronicles Samuel’s birth, subsequent illness, disability, and death along with his enduring piety. The last chapter contains something particularly interesting.

The author indicates that Samuel died while she was preparing the book. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. Much to my surprise, the book has very detailed directions to his gravesite and an open invitation to visit it. I have never seen anything like it.

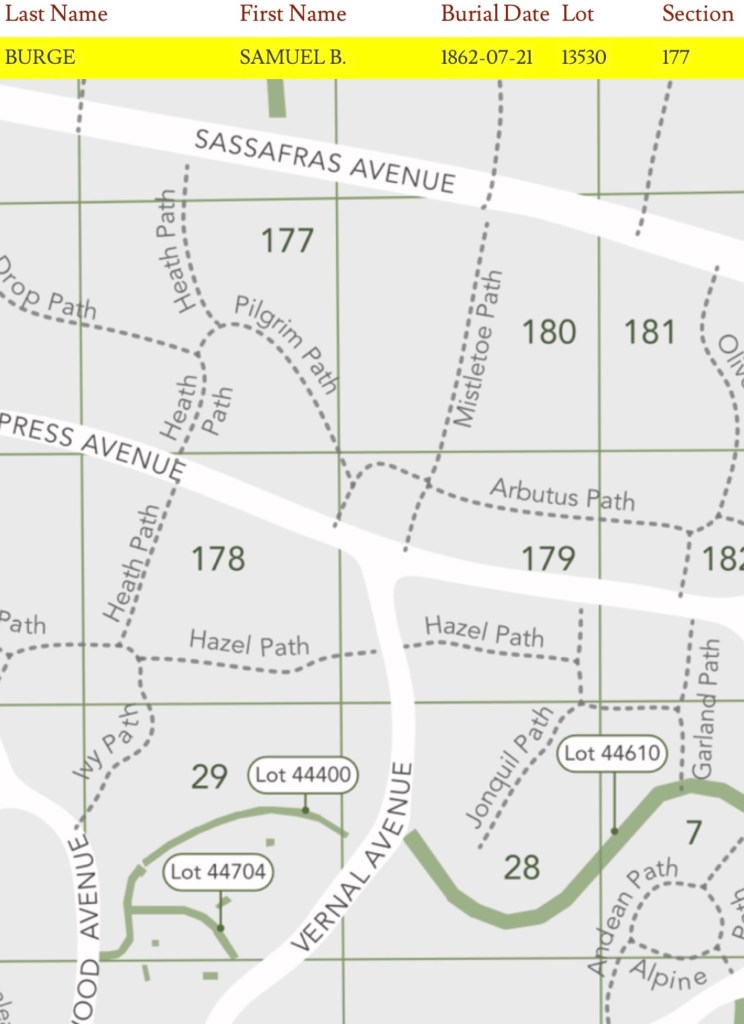

Did you ever visit Greenwood? If you go there some day when the spring-time comes again, dear children, and happen to be in “Cypress Avenue,” near “Vernal,” between “Pilgrim Path” and ” Mistletoe” perhaps you will like to visit my little minister’s grave. I think you will find “Brentie” upon the tombstone – his name was “Samuel Brenton” – but “Brentie” was the sweet pet name by which we always called him, and that is what we want to see upon his monument.

Little Samuel’s Ministry, page 30

I found a map of Green-Wood Cemetery and those avenues and paths really exist. Their historical records contain the burial information for Samuel B. Burge. It says he was buried in section 177 which includes the area around Pilgrim path and Mistletoe path. 5

I was also able to confirm that Samuel is the author’s brother using other genealogical and historical records.6 I am not sure if the headstone for “Brentie” still stands. If you have any information, please let me know.

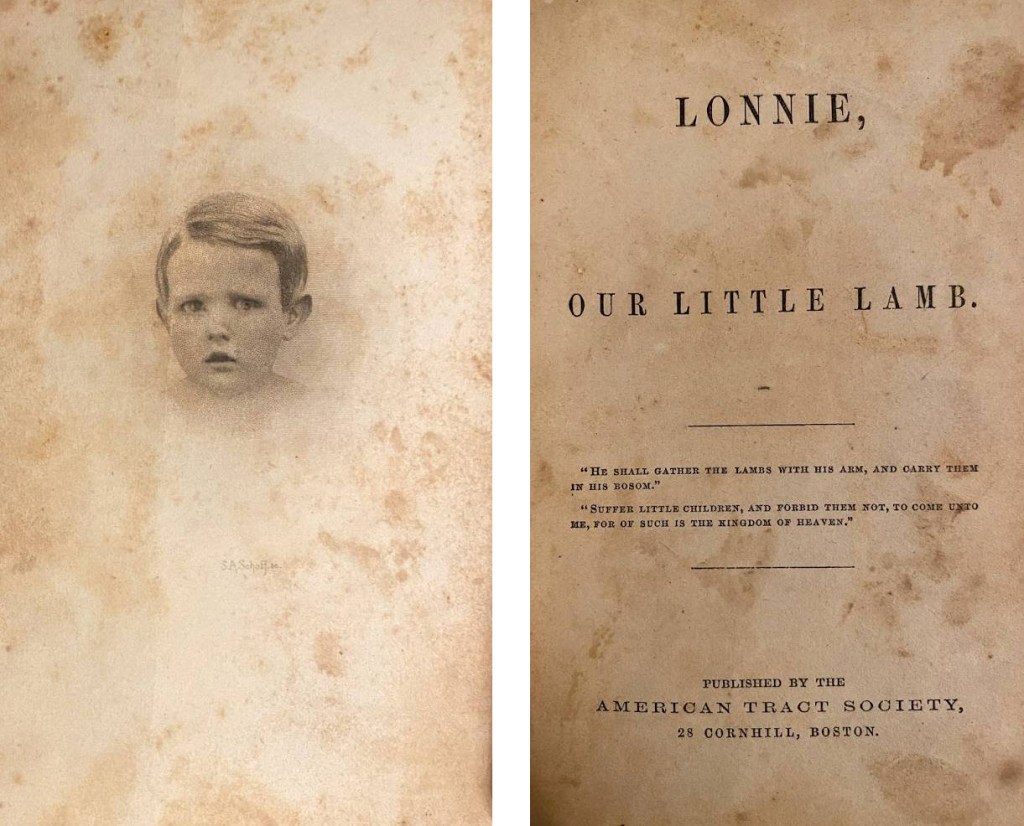

Alonzo Frederic Brown

I also recently acquired Lonnie Our Little Lamb, which was published around the same time. It was written by another Brooklyn resident, Mrs. Helen E. Brown. The book is about her son, Alonzo Frederic Brown, who was affectionately known as Lonnie. The frontispiece contains a lifelike image of the boy produced by Stephen A. Schoff.

The book frankly discusses the reality of death and depicts Lonnie inquiring about the deaths of friends and family. Throughout it all, his mother explains the basics of their Christian faith and he is comforted by it.

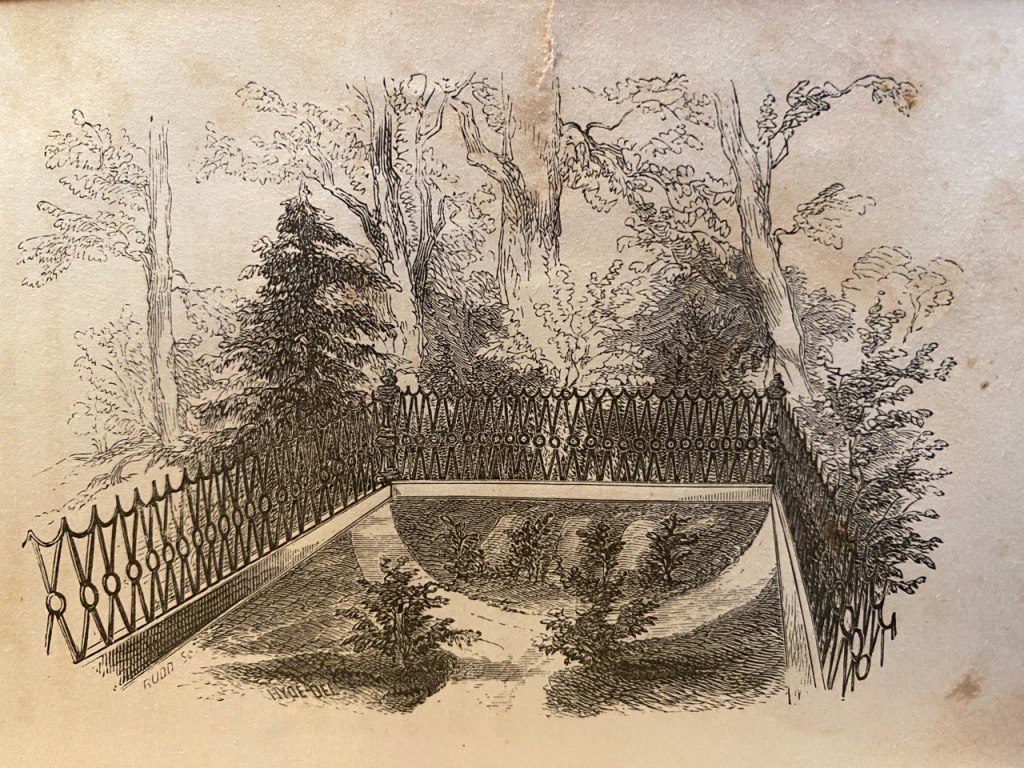

Lonnie dies of Diphtheria shortly before his fifth birthday. The end of the book mentions that he was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery and even includes an image of his burial plot.

I was able to find his burial information in Green-Wood Cemetery’s historical records. He was buried in lot number 5083 on March 5th, 1861.7 His residence at the time was 146 Columbia in Brooklyn, New York.8

Lillie Rose Brown

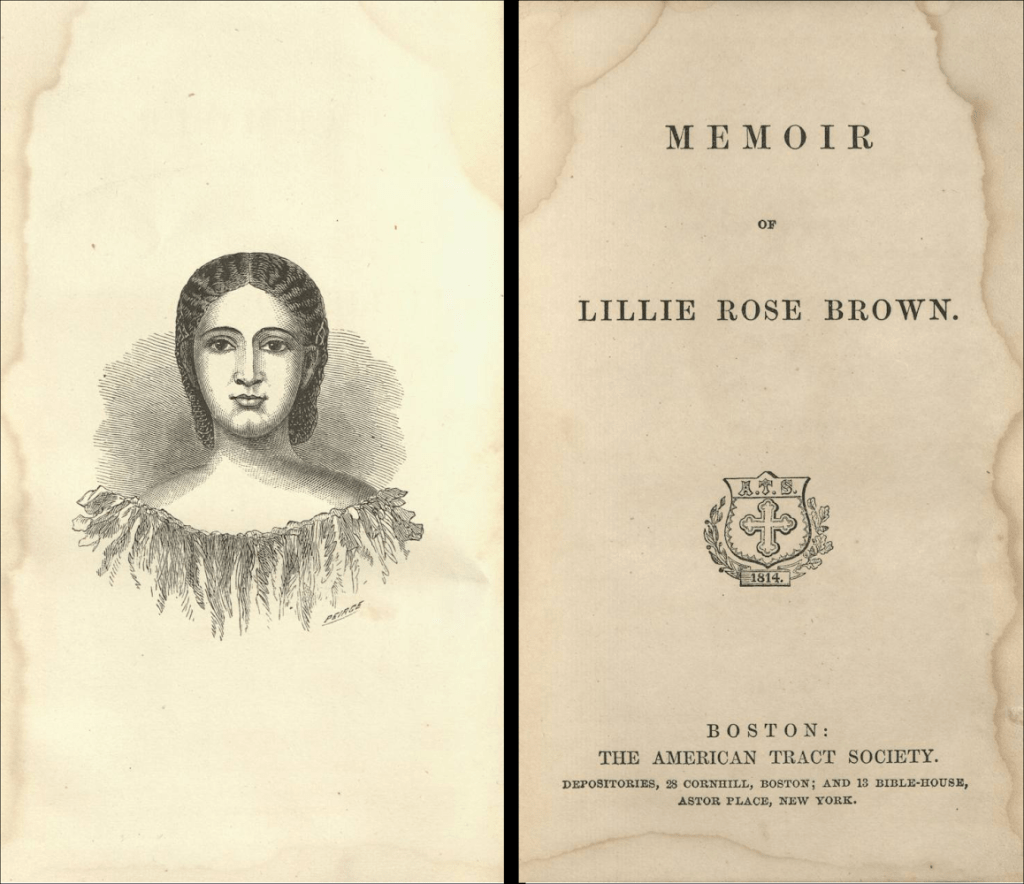

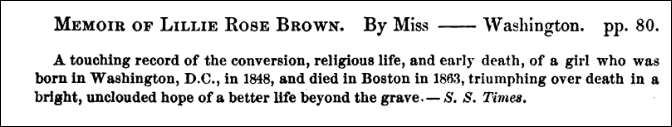

During the American Civil War and Reconstruction, several books were written specifically for formerly enslaved people. Memoir of Lillie Rose Brown was one such book. It was the second installment of a series titled The Freedman’s Library. The first book in the series was John Freeman and his Family by Helen E. Brown.9

Memoir of Lillie Rose Brown

Lillie Rose Brown was a real person. She was born in Washington, D.C. and died in Boston in 1863 at the age of fifteen.10 This account of her life was published just a few years later, in 1866. It describes her conversion and enduring piety throughout recurring illnesses and death. She personally knew Reverend Leonard Grimes and attended 12th Baptist Church. I’ve been able to confirm this basic biographical information, though other aspects of the book remain a mystery.

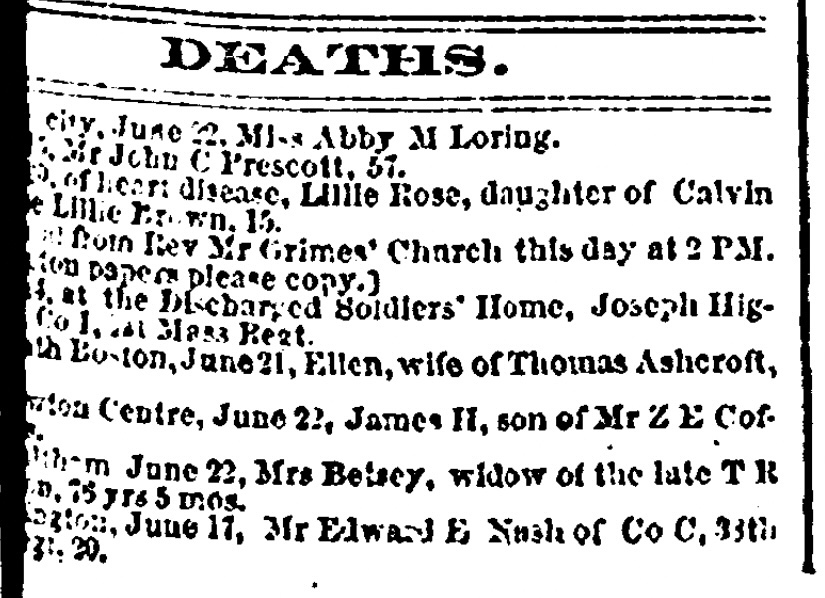

June 20, of heart disease, Lillie Rose, daughter of Calvin and Rose Lillie Brown, 15. (Funeral from Rev Mr Grimes’ Church this day at 2 PM. Washington papers please copy.)

Daily Evening Traveller, June 24, 186311

Unfortunately, the author of the book is not clearly identified. The 1866 annual report for the American Tract Society in Boston lists the author as Miss ______ Washington.12

But the last page of the book contains the initials A.A.D.

In other publications by the American Tract Society in Boston, Alice A. Dodge signed her work with her initials. That is technically a possibility, but it seems unlikely since the book contains intimate details of the girl’s life and Dodge lived in a neighboring state. I’m not quite sure what is going on here.

Any information about Lillie Rose Brown and this book would be most welcome.

Notes

1 – Diana W. Pasulka, “A Communion of Little Saints: Nineteenth-Century American Child Hagiographies,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 3, no. 2 (2007): 51–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20487898

2 – Fiftieth Annual Report of the American Tract Society Presented at Boston, May 25, 1864, (Boston: American Tract Society, 1864), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015034588650&view=1up&seq=1.

3 – Willard, Frances E., and Mary A. Livermore. A Woman of the Century. Buffalo: Charles Wells Moulton, 1893. https://archive.org/details/womanofcenturyfo00will/page/342/.

4 – You can read Old Wickford online courtesy of the Library of Congress. The portrait of Reverend Lemuel Burge is from an unnumbered page between 172 and 173. https://archive.org/details/oldwickfordtheve00gris

5 – You can view the historical records for Green-Wood Cemetery on their website: https://www.green-wood.com/burial-and-vital-records/

6 – I have built a public family tree for Francis Irene Burge Smith on Ancestry. You can view it here: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/194488078/

7 – Green-Wood Cemetery records; see link above.

8 – I have built a public family tree for Helen E. Brown on Ancestry. You can view it here: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/194487933/

9 – Brown, Helen E. John Freeman and His Family. Boston: American Tract Society, 1864.

10 – “Lilly R. Brown in the Massachusetts, U.S., Death Records, 1841-1915,” Ancestry, 2013, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/7393032:2101?ssrc=pt&tid=194487851&pid=412539437306.

I have built a public family tree for Lillie Rose Brown on Ancestry. You can view it here: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/194487851/

11 – “Deaths,” Daily Evening Traveller, June 24, 1863.

12 – Fifty-Second Annual Report of the American Tract Society Presented at Boston, May 30, 1866. Boston: American Tract Society, 1866. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015034588643&view=1up&seq=3.