As you may have already surmised, I have been almost completely consumed by my attempts to trace the reuse of illustrations around the world between 1860 and 1880. This post will explore a unique set of papers all modeled after a London newspaper titled The British Workman.

The British Workman and Friend of the Sons of Toil

February 1855 1

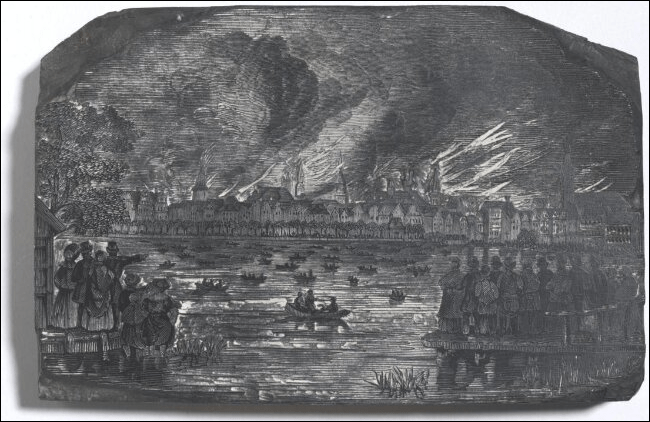

But first – let me quickly introduce you to the art and science of printing in this time period. We currently live in a world where it is possible to capture, duplicate, and transmit images all around the world in the blink of an eye. The 19th century was nothing like that. There were some photographic processes available: daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes. But no one had the technology to mass produce photographs and integrate them into newspapers. If you wanted to print an illustration, it had to be hand carved and essentially used as a giant stamp. A few different methods were used, but during the 1860s-1880s wood block engraving dominated the market.

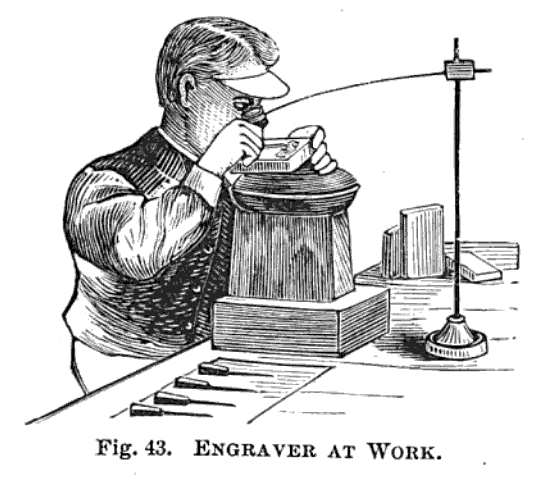

Engraving in this period typically involved two individuals. An artist would sketch the image directly onto a wood block and an engraver would carefully carve it out. This required extraordinary precision, so they typically worked while looking through a magnifying glass as depicted below.

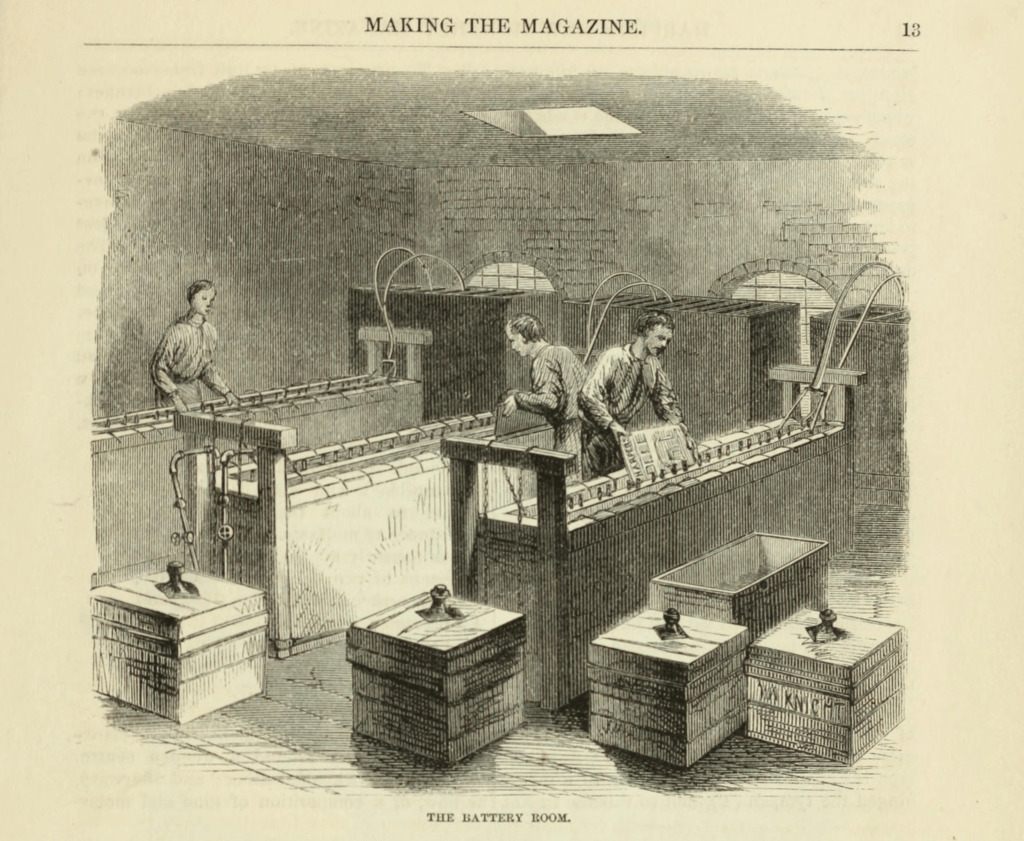

The wood used to create the engravings is very sturdy, but not impervious to the intense pressure needed to print it. It would wear out if subjected to thousands of printings. Therefore many publishers opted to create a metal duplicate of the image via electrotyping. This allowed them to create several copies of a single image and also created a more durable printing plate. If you want to read more about this process, I recommend the article “Making the Magazine” published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in December 1865.

Since creating an illustration took so much effort, publishers naturally wanted to reuse them whenever possible. The makers of The British Workman were no exception. It was a cheap monthly newspaper created by a fascinating man named Thomas Bywater Smithies. He was a devout Methodist and social reformer.

He was devoted to the temperance cause but quickly realized the limitations of traditional tract distribution. So he decided to create something radically different: a monthly illustrated newspaper so attractive that working class people would treasure it.

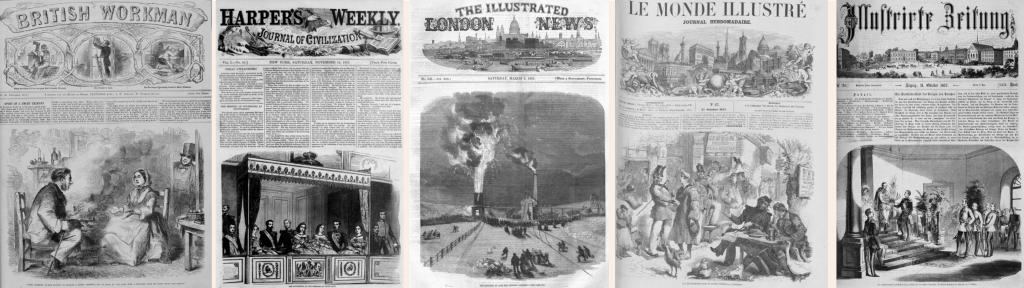

The first issue of The British Workman was published in February 1855. The price was just one penny and every issue contained beautiful illustrations that rivaled leading publications like Harper’s Weekly, The Illustrated London News, Le Monde Illustré, and Illustrirte Zeitung. The illustrations in The British Workman were created by prolific period artists like Henry Anelay, Robert Barnes, Harrison Weir, John Gilbert, and Birket Foster.

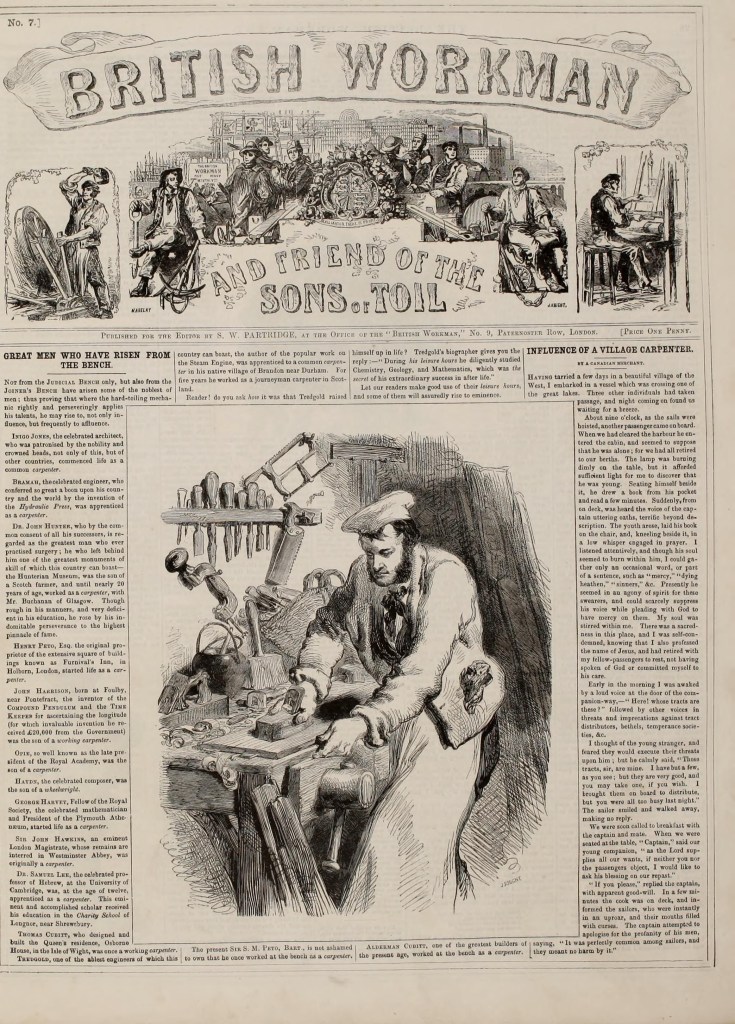

My favorite illustrations are the ones of skilled workers. The first year featured a series of articles about various skilled workers: carpenters, stone masons, blacksmiths, barbers, and more. The illustration below depicts a carpenter at a traditional workbench. The accompanying article describes a host of professionals with a connection to carpentry.

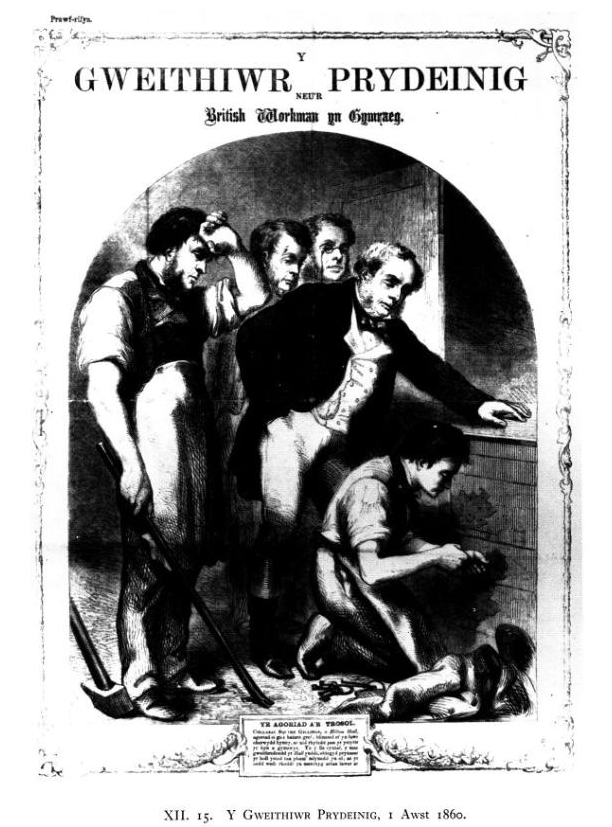

It took over two years for The British Workman to gain a firm footing, but eventually it did. In the 1860s they decided to expand by offering copies translated into different languages. The experiment began with a translation into Welsh. It was announced as Y Gweithiwr Cymreig8 but it actually appeared with the title Y Gweithiwr Preydeinig. It appears the project was quickly abandoned due to a lack of subscribers.9

August 186010

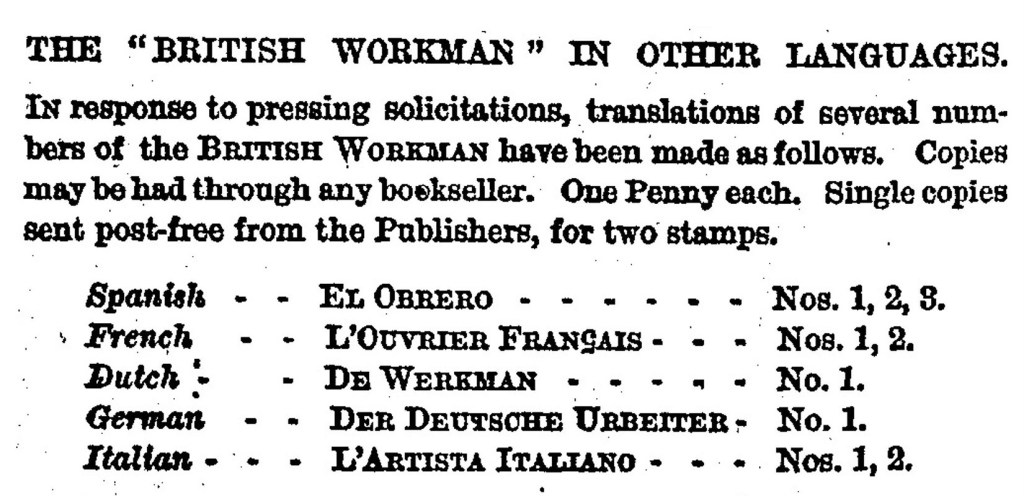

They tried foreign languages again in 1868 and seemed to be more successful. They began by offering just a few languages: Spanish, French, Dutch, German, and Italian. Each one had a specialized title.

They added several additional languages in subsequent years. Here is the full list of papers that I’ve been able to identify.

L’Ouvrier Français (French)

Mpiasa Malagasy (Malagasy)

Y Gweithiwr Prydeinig (Welsh)

El Obrero (Spanish)

[Unknown] (Norwegian)

Rzemieslnik Polski (Polish)

Der Deutsche Urbeiter (German)

De Werkman (Dutch)

L’Artista Italiano (Italian)

[Unknown] (Portugese)

[Unknown] (Russian)

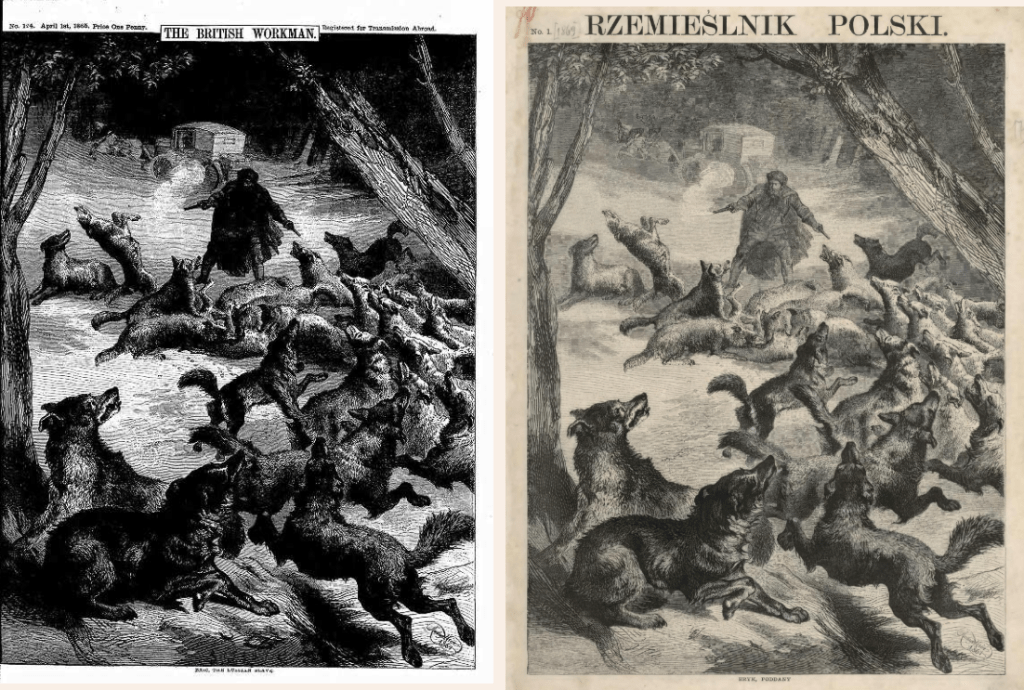

So far I’ve only seen a complete issue of the Polish paper: Rzemieslnik Polski. Even though I don’t speak Polish, it is readily apparent that the content is not exactly the same as the corresponding English edition. I am currently trying to get digital copies in other languages so I can do a more complete analysis.

The 1870s brought another experiment: lending printing plates to other publishers. These papers were modeled after The British Workman, reused its illustrations, but were published in other countries. Each of them has a unique background and distinct editorial style. So far I’ve only found three:

The Southern Workman

Den Norske Arbeider

Русский Рабочий (Russkiy Rabochiy)

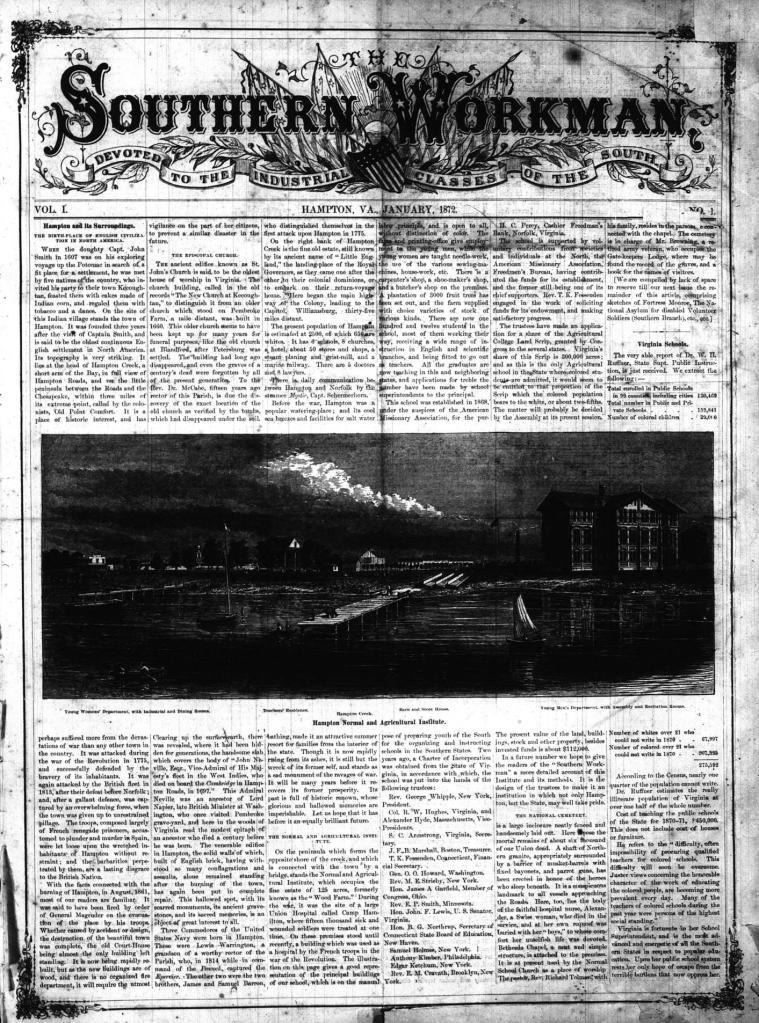

The Southern Workman began publication in January 1872. It was published in Virginia at the Hampton Institute, a historically black college founded by the American Missionary Association after the Civil War. As such, the intended audience for this paper was Black Americans. It included contributions by noteworthy Black authors like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper as well as a variety of correspondents. In it’s early years, the publishers of The Southern Workman didn’t have the ability to create their own illustrations; they relied entirely on donations. In an article from December 1872, they acknowledge that their illustrations came from several different publishers. So far I’ve identified images originally created by the American Tract Society in New York, The American Tract Society in Boston, and S. W. Partridge & Co. (publishers of The British Workman.) 14

It’s worth noting that Partridge might not have given the plates directly to The Southern Workman. I suspect Partridge initially gave the plates to the American Tract Society in New York, then the Society gave them to The Southern Workman.15 That being said, the folks at The Southern Workman were well aware of The British Workman. They reprinted at least one of their articles.16 I’m still exploring the connections between these papers and hope to find more details in the future.

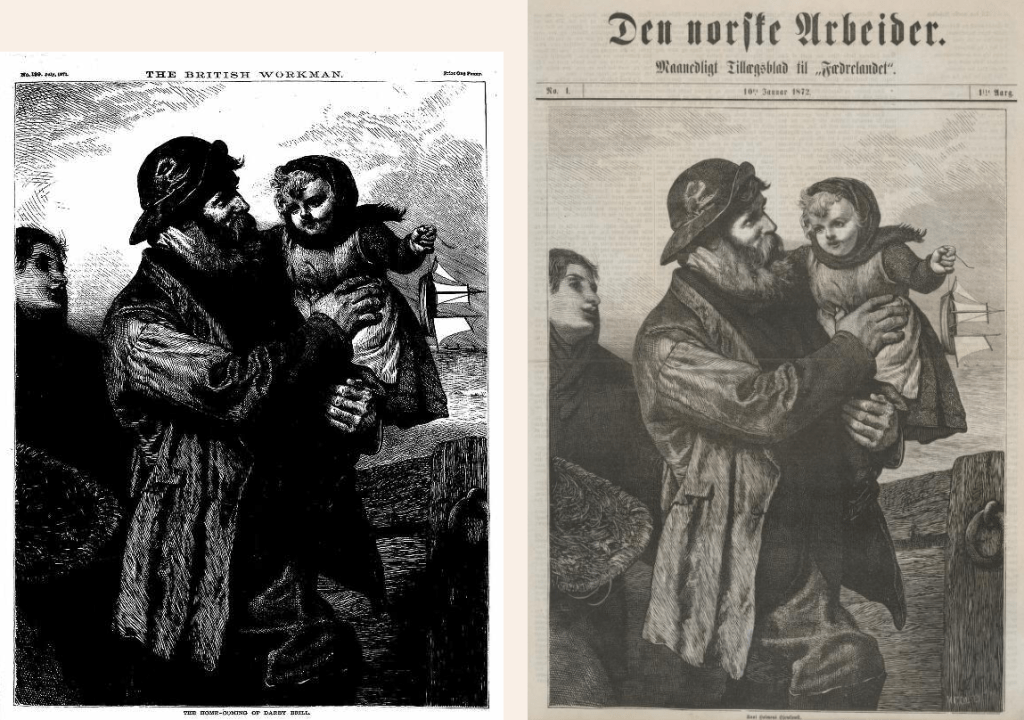

Den Norske Arbeider (The Norwegian Workman) also began publication in January 1872. It was edited by a Lutheran minister named Peter Lorenzen Hærem. He visited London in 1870 and personally met Smithies. So presumably Hærem made an agreement directly with him. During its first year of publication, it used many illustrations from The British Workman but the content appears to be quite different.

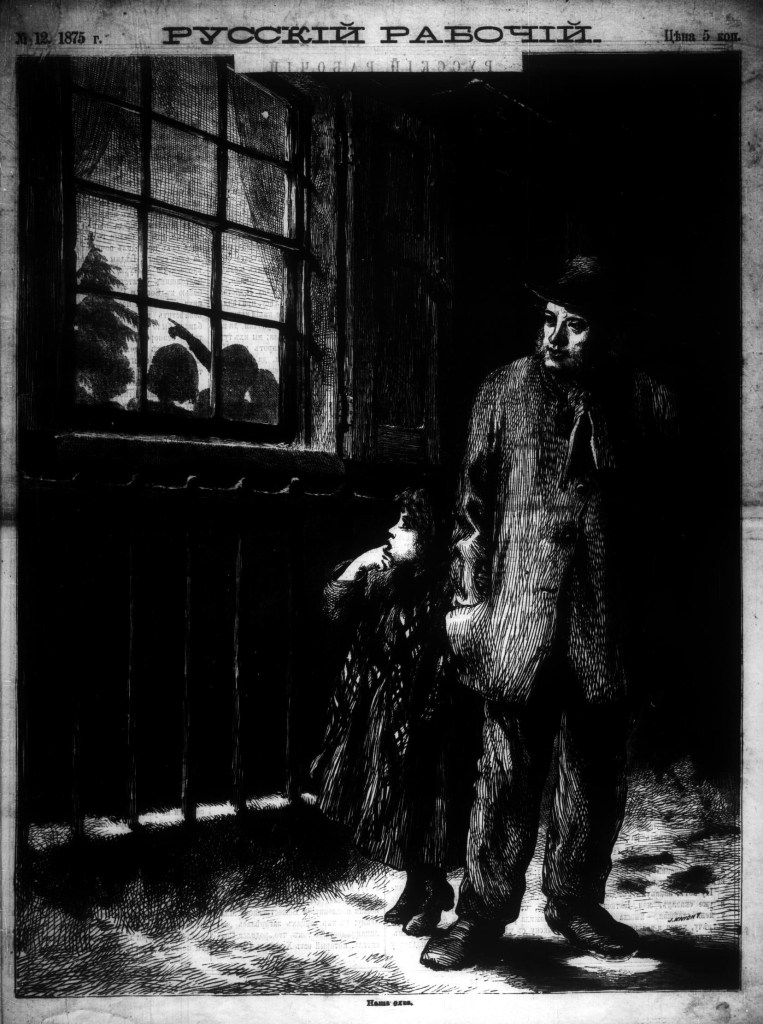

Русский Рабочий (Russkiy Rabochiy / Russian Workman) was edited by Мария Григорьевна Пейкер (Maria Grigorievna Peiker). She became an evangelical Protestant after hearing Dwight L. Moody speak in London. This put her somewhat at odds with ecclesiastical censors but she persisted. Her paper included contributions by Russian Orthodox clergy and Russian literary figures. I’m not sure who gave the engravings to her. I know she received some support from the London Religious Tract Society, so she clearly had some close contacts in the city.19 While her paper reused illustrations from The British Workman, its content appears to be unique.

December 187520

As you can see, The British Workman made its way all around the world. It remains to be seen if there are yet more papers out there, waiting to be discovered. I essentially stumbled across all of this by accident. If you have any information that might be helpful to me, please contact me.

Footnotes

- You can view all the issues of The British Workman from the first ten years at this link: https://archive.org/details/britishworkman1119lond/page/n11/mode/1up ↩︎

- Illustrated London News. Wood Block for the First Number of “The Illustrated London News.” Wood-engraved block. Victoria & Albert Museum Prints, Drawings & Paintings Collection. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O747717/wood-block-for-the-first-printing-block-illustrated-london-news/.

↩︎ - Emerson, William Andrew. Hand-Book of Wood Engraving: With Practical Instruction in the Art for Persons Wishing to Learn Without an Instructor; Containing a Description of Tools and Apparatus Used, and Explaining the Manner of Engraving Various Classes at Work, Also, a History of the Art, from Its Origin to the Present Time. Lee and Shepard, 1881. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Hand_book_of_Wood_Engraving/sJBKICvihHEC?hl=en&gbpv=0.

↩︎ - Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. “Making the Magazine.” December 1865. https://archive.org/details/harpersnew32various/page/18/mode/1up.

↩︎ - Rowe, George Stringer. T.B. Smithies : Editor of “The British Workman” : A Memoir. London : S.W. Partridge, 1884. http://archive.org/details/tbsmithieseditor00rowe. ↩︎

- The British Workman (London). “Story of a Smokey Chimney.” December 1857. https://archive.org/details/britishworkman1119lond/page/141/mode/1up.

Harper’s Weekly (New York). “The Sovereigns at the Theatre at Stuttgardt.” November 14, 1857. https://archive.org/details/sim_harpers-weekly_1857-11-14_1_46/mode/1up.

Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig). “Die Zusammenkunst Des Kaisers Franz Joseph Mit Dem Kaiser Alexander Auf Scloss Belvedere Bei Weimar Am 1. Oktober.” October 31, 1857. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=cub.u183024040381&seq=295&view=1up.

Le Monde Illustré (Paris). “Les Enrolements Pour Le Service Militaire, a Londres.” October 17, 1857. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb32818319d/date.

The Illustrated London News (London). “The Explosion at Lund Hill Colliery, Barnsley.” March 7, 1857. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015010948779&seq=196&view=1up. ↩︎ - The British Workman (London). “Great Men Who Have Risen From the Bench.” August 1855. https://archive.org/details/britishworkman1119lond/page/25/mode/1up.

↩︎ - The British Workman (London). “Notice to Correspondents.” September 1860. https://newspaperarchive.com/british-workman-sep-01-1860-p-2/.

This article states the title of the Welsh edition was titled Gweithiwr Cymreig. The only extant copy has the title Y Gweithiwr Preydeinig. ↩︎ - The British Workman (London). “Welsh British Workman.” October 1860. https://newspaperarchive.com/british-workman-oct-01-1860-p-2/.

This article states that they have not received the requisite 20,000 subscriptions yet and asks for more to be received by the end of the month. There are no updates given in November or December, so it appears the project was abandoned. ↩︎ - The only copy of that I’ve located is at the Welsh National Library. I’m working on getting a clear digital copy. This image is from the following article:

Jones, E. D. “News and Notes. Y Gweithiwr Preydeinig Neu’r British Workman Yn Gymraeg.” The National Library of Wales Journal (Aberystwyth) 12, no. 4 (1962). https://journals.library.wales/view/1277425/1281889/97#?m=42. ↩︎ - The British Workman (London). “The ‘British Workman’ in Other Languages.” March 1869. https://newspaperarchive.com/british-workman-mar-01-1869-p-2/. ↩︎

- Rzemieslnik Polski (London). “Eryk, Poddany.” January 1869. https://archive.org/details/jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl.NDIGCZAS000192_1869_001/mode/1up.

The British Workman (London). “Eric, the Russian Slave.” April 1864. https://newspaperarchive.com/british-workman-apr-01-1865-p-1/. ↩︎ - Southern Workman (Hampton, VA). “Seedtime and Harvest.” February 1873. https://archive.org/details/SouthernWorkman18721880/page/n52/mode/1up.

The British Workman (London). “The Sower.” February 1871. https://newspaperarchive.com/british-workman-feb-01-1871-p-1/.

Русский Рабочий (Санкт-Петербург (St. Petersburg)). “Сѣятель.” January 1875. https://archive.org/details/per_russkiy-rabochiy_-_1875/page/n1/mode/1up. ↩︎ - Southern Workman (Hampton, VA). “Acknowledgements.” December 1872. https://archive.org/details/SouthernWorkman18721880/page/n45/mode/1up. ↩︎

- Many illustrations from The British Workman were used by the American Tract Society in New York. I’ve found several examples from their periodical Illustration Christian Weekly. More research is needed to confirm if the Society later donated those engravings to The Southern Workman. ↩︎

- Southern Workman (Hampton, VA). “With All His Might.” April 1872. https://archive.org/details/SouthernWorkman18721880/page/n14/mode/1up. ↩︎

- Southern Workman (Hampton, VA). “Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute.” January 1872. https://archive.org/details/SouthernWorkman18721880/mode/1up.

↩︎ - The British Workman (London). “The Home-Coming of Darby Brill.” July 1871. https://newspaperarchive.com/british-workman-jul-01-1871-p-1/.

Den Norske Arbeider (Christiania). “Knut Holmens Hjemkomst.” January 10, 1872. https://www.nb.no/items/afd9e7659e94b00764962857ac9d9653. ↩︎ - Religious Tract Society Record (London). “Russian Workman.” March 1881. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Religious_tract_society_record_of_wo/qjoEAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=RA5-PA7. ↩︎

- Русский Рабочий (Санкт-Петербург (St. Petersburg)). “Наша Елка.” December 1875. https://archive.org/details/per_russkiy-rabochiy_-_1875/page/n45/mode/1up. ↩︎

Edit Log

This article was last edited on January 28, 2026.